Delaware State University History Series: The 1962 Hollywood Diner sit-in

This is the first installment of the new Delaware State University History Series, which highlights the stories and people who have played a part in the 129-year higher education journey of this institution.

Del State and UD Students’ 1962 stand against segregation

By Carlos Holmes

In the days of segregation, if Del State students wanted to grab something to eat off campus, the social norms of that day did not allow them to sit down and eat in any of the restaurants on DuPont Highway.

They could only purchase food for take-out. At certain restaurants, they were not even allowed to go inside and pick up their order, but instead had to suffer the additional indignity of having to get their order at the back door of the restaurant.

However, in 1962 in interracial group of seven students from then-Delaware State College and the University of Delaware entered the Hollywood Diner and sat down to be served. Their act against the segregation of that time ended in their arrest.

This story in the civil rights history of Delaware was part of the growing pressure in the early 1960s to end segregation in public places.

In the previous decade, Delaware had been cast in a harsh national spotlight of the over vehement opposition to an unsuccessful attempt to integrate Milford High School in 1954. The state received international glare in 1957, when a Howard Johnson Restaurant – about a quarter mile north of the Hollywood Diner – refused to serve visiting Finance Minister Komla Agbedi Gbedemah from Ghana and his entourage, prompting a personal apology to the African official from then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Fast forward to 1962, when the Hollywood Diner was in its 29th year of existence as a restaurant –one that had always prohibited blacks from dining there. The Delaware Code’s “Innkeeper Law” sanctioned the restaurant’s discrimination, which stated that an establishment owner had the right to refuse service to anyone who would be offensive to the majority of the customers at the establishment.

In early 1960s, an organization called the Student Committee Against Discrimination existed at both Delaware State College and the University of Delaware. From those groups, seven students – three African Americans from DSC and an African American male along with two white males and a white female from UD – came together to challenge the Innkeeper Law.

From DSC, the students were Roland E. Livingston, Jesse A. Blackshear and Linda G. Anderson. From UD, the students were Philip Myrle Anderson, Elizabeth A. Pilat (now Marston), Duane C. Nicholas, and James White.

Dr. Livingston was the nephew of state Rep. Paul Livingston – the second African American to serve as a legislator in the history of the Delaware General Assembly. Rep. Livingston had introduced a public accommodations bill in the House of Representatives, but the legislation was buried in a legislative committee at the time of the sit-in.

“We decided to stage the sit-in, because we felt it was a way to bring attention to the need to get passage of my uncle’s bill,” said Dr. Livingston, who was a Del State sophomore at that time .

At least some of the group previously had entered a segregated restaurant in northern New Castle County, but to their surprise, they were served. They then decided to focus their attention on the state capital.

On Feb.10, 1962, this interracial group entered the Hollywood Diner, about two miles south of the DSC campus on DuPont Highway. According to court documents, the cashier on duty told one of the group members as they entered “We can’t serve you in here… we just don’t serve colored people in here.” Undaunted, the group sat down at two tables and refused to move, despite being asked repeatedly to leave.

“The owner told us ‘I’m Jewish and I know where I belong, and you don’t belong here’,” Mrs. Marston recalled.

The Delaware State Police were called and two troopers arrived. The officers were armed with two volumes of the Delaware Code, brought per the directive of their commander. After the manager once again asked the interracial patrons to leave in the presence of the police, State Police Lt. James T. Vaughn – who would later become a prominent state senator – identified himself to the students and showed them the sections of state law that applied to the Innkeepers Law and the offense of trespassing.

The students were then arrested, charged with trespassing and locked up in a local jail.

“The interesting thing about being locked up was that we were segregated in jail by race,” Mr. Livingston said.

Being arrested for the sit-in was no surprise to the DSC students. Prior to the incident, they met with Louis Redding, the legendary civil rights attorney and the first African American to practice law in the State of Delaware. He made sure the students understood the likelihood of their arrest. He also agreed to represent them.

“We thought we’d make a greater impression on the people of the area if we went to jail,” Mr. Blackshear told reporters at the time.

However, the trip to jail was an unexpected development for at least one of the UD students.

“You know if you are breaking the law, you have to face consequences. But going to jail was never discussed,” Mrs. Marston said. “I didn’t anticipate being alone in jail, but it would not have dissuaded me if I had known before.”

Because of the jail segregation, she and Ms. Anderson was separated in different cells. “I could look out my cell window in the Dover jail and see the whipping post outside,” Mrs. Marston said. “It was surreal.” The whipping post – which had not been used since 1952 – still existed at that time outside of the Dover jailhouse.

The students were in jail one night and released the next day after a group of local black residents provided the money to post bail for all seven. Because the group waived a jury trial, the case went before Court of Common Pleas Judge William G. Bush III in June of that year.

While Dr. Livingston said that Del State students were generally supportive of what they had done, Mrs. Marston said the UD Student Council took the opposite view of their actions. “They said we embarrassed the university and wanted us to come before the Student Council to give an accounting of ourselves,” she said. “I wanted to do that, but James White, who was leading the UD students in the sit-in, refused to do it; so I followed his lead.”

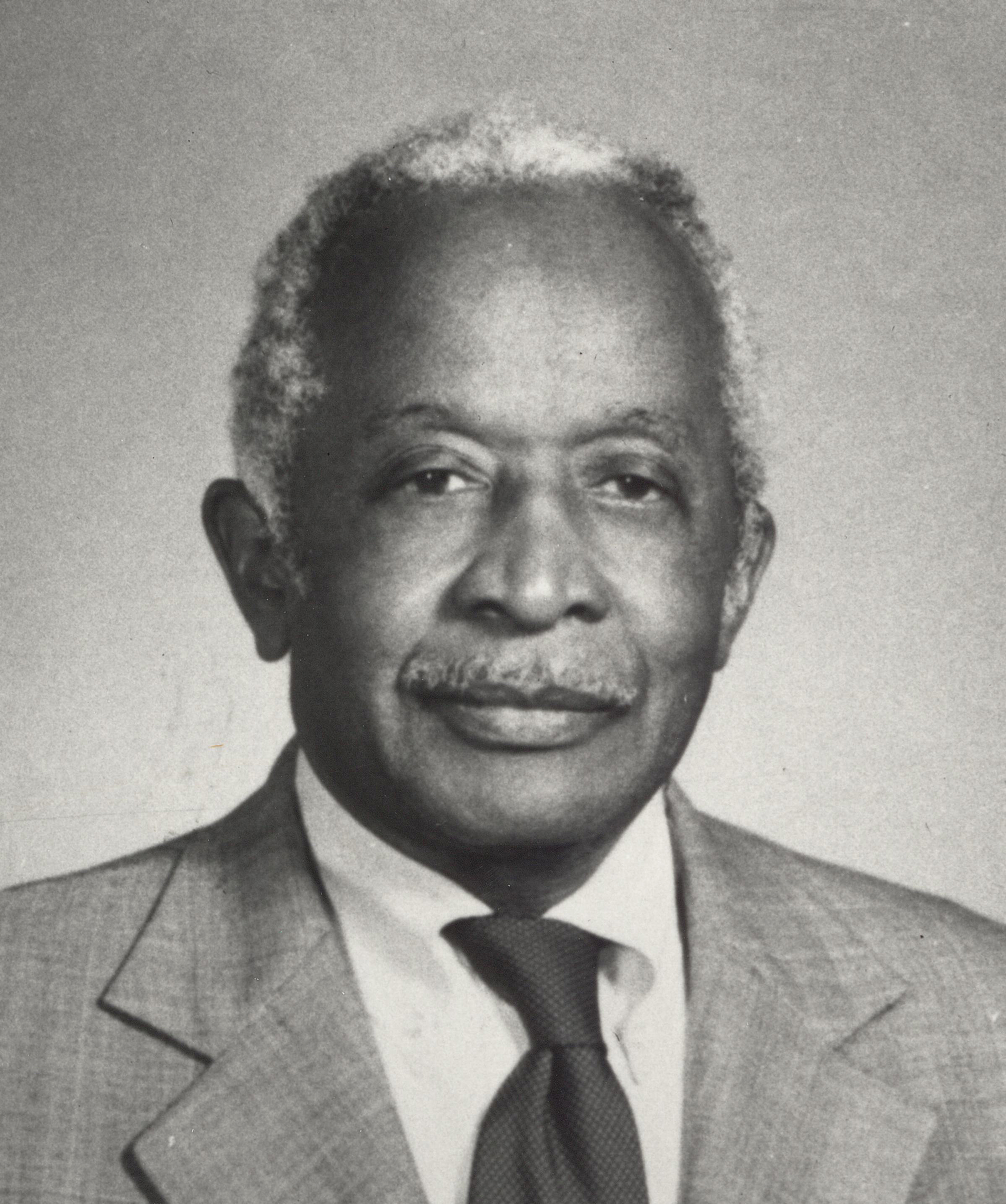

The group’s attorney had already established a name for himself as a prominent civil rights attorney. Mr. Redding had won a 1950 case that forced the University of Delaware to admit black students, and he was a part of Thurgood Marshall’s winning legal team in the landmark 1953 Brown v. Board of Education. Mr. Redding also successfully argued the 1961 Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, another Delaware public accommodations case.

“Louis Redding told us, ‘I’ve been waiting on you people for a long time,’ talking about whites getting involved,” Mrs. Marston said.

Before Judge Bush, Mr. Redding showed his legal mastery by arguing the following convincing points:

- Because the “Innkeepers Law” stated that a proprietor is not obligated to serve persons whose presence would be “offensive” to the major part of its customers and would injure his business, the State Police did not establish that the students’ action met the law’s criteria of offensiveness to other patrons. The troopers only assumed that it had, and therefore based their arrest on that assumption.

- That the racially discriminatory action by the troopers violated the defendants’ Fourteenth Amendment equal civil rights, and that a conviction of the defendants would be a violation by the state judiciary of the same constitutional rights.

- Because state controls such as public health laws and business licensing exist for public protection, public facilities such as restaurants do not have the right to indulge in racial discrimination. Because the defendants were also members of the public and sought the same dining service afforded to others, no trespassing occurred.

Judge Bush did not rule on the case until November 1963 – about 21 months after the Hollywood Diner sit-in occurred. Nevertheless, the judge found the entire group innocent of the trespassing charges, and further ruled that it was unconstitutional for a business owner to ask the government to enforce a private policy of racial discrimination.

By that time, the Hollywood Diner already had done away with its discriminatory policy and served to all members of the public.

Sadly, Rep. Livingston passed away earlier that year without seeing his public accommodation legislation become a reality. However, his successor – then-Rep. Herman Holloway – continued to champion the legislation. In December 1963 – one month after Judge Bush’s ruling – the State of Delaware passed and enacted House Bill 466, which made public accommodations discrimination illegal, effectively eliminating the institutionalized sanction of that Jim Crow policy in the First State.

For Dr. Livingston, it was a bittersweet achievement. “My uncle never got to see the passage of his legislation,” he said.

Dr. Livingston, who graduated from Del State in 1964 with a BS in History and a minor in Business Administration, said then-DSC President Luna I. Mishoe had the dual challenge of maintaining good relationship with the state legislators while at the same time honoring students’ First Amendment rights.

“Dr. Mishoe was a great president who did not actively discourage or participation, nor did he actively encourage it,” Mr. Livingston said. “I think there was a general understanding that we would not bring any bad press on the school.”

Dr. Livingston would go on to earn an Ed.D., teach at various universities and working as a human resources administrator. He currently heads Livingston & Associates, and organizational development consultant firm.

Linda G. Anderson graduated in 1967 with a BS in Elementary Education. Her post-graduation years are unknown.

Jesse Allen Blackshear would go on to become a prominent minister in Savannah, Ga.

Duane Nichols is a retired professor of chemical engineering in West Virginia.

James White, who later became a teacher, is deceased.

Philip Myrle Anderson was a UD track star, who was later inducted in the Delaware Track and Field Hall of Fame. He is deceased.

Betsy (Pilat) Marston went to become a Emmy-award winning documentary film producer, and later along with her late husband Edwin Marston founded the publication of two newspapers that were later combined into the magazine High Country News. At age 79, she is still actively involved with the journalism of the publication.

Former Dover Post journalist Jeff Brown contributed information for this article.

The photo of Louis Redding was provided courtesy of the Delaware Historical Society Collections (PPLR64)